IT SHOULD BE NOTED THAT THE VIEWS EXPRESSED HERE ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR AND NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF AFG VENTURE GROUP

Glen Robinson B.Sc.[Tech] JP

Glen is a co-founder of Asean Focus Group P/L [now AFG Venture Group] which was formed in 1990 to provide advice and assistance to those organisations which wished to take a commercial presence in Asean. It has been incredibly successful in actually being effective and consequently we have a very presentable client list. Additionally, we have worked with the Indonesian BKPM, Thai BOI, Malaysian MIDA and Myanmar MIC, and other investment agencies in relation to their inward investment policies and strategies. Throughout this process we have developed a deep network of colleagues in the region in both government and the private sectors.

Glen has been on the boards of many Asian related business organisations and has for many years advised a number of Foreign Investment Boards in the ASEAN region.

He initially gained his South East Asian experience as chief executive officer for the Asian subsidiaries and joint ventures of a major International manufacturing and marketing organisation.

1. INTRODUCTION

Australia’s commercial relationship with Asia is underwhelming given the proximity of our 2 regions and the rhetoric which has been expounded over 2 decades. Despite considerable entreaties from a range of well-informed commentators, both our trade and investment performances have been disappointing at best. After 30 years of advising and assisting companies to take a commercial interest in ASEAN, it is personally disappointing to see this comparatively low level of commercial activity.

Many reasons have been promoted for this lack of commercial engagement, but none seem to have sufficient traction to be credible in its own right.

In recent years corporate Australia has tended to regard this region as a homogeneous entity without recognising the significant differences and opportunities between the individual countries, and those same corporates have demonstrated a reluctance to invest and establish operations in this region. The more recent fascination with China has been quite interesting as it has produced a love/hate attitude which is not conducive to reasoned nor articulated investment strategies.

This paper purports to look at the issue from several perspectives,

- The present situation,

- why should Australian Corporates be expanding into the region?

- the reasons given by various people as to why there is this reluctance to do so, and

- and explores the credibility of those reasons for why there is reluctance

The result is quite enlightening, in that none of the reasons are credible.

A subsequent paper discusses the various resources we have to provide further information on the countries in the region, what those countries may offer, and the means to take advantage of those opportunities.

2.WHERE ARE WE IN RELATION TO ASIA?

There have been a number of articles, presentations and analyses which clearly demonstrate we are avoiding Asia, and probably the most notable was the PwC “Passing Us By” [1] which had a significant impact in the Australian market, and almost certainly spawned a number of follow up articles. Additionally, the OECD has noted that Australia has among the lowest level of commercial activity in foreign markets [2] and this applies for both investment as well as exports.

But the first step in this process is to establish where do Australian corporates actually invest.

Sometimes it is difficult to identify the actual source of an investment, as many investments are made through 3rd countries, see World Investment Report 2017 [3].

With that as a caveat, the average movements in FDI for the 3 years 2014-2016 is as follows:

Inward FDI was $US 35,998 [million],

Outward FDI was $US 1,615 [million].

The target countries by value were USA [28 %], UK [16%] and Japan [5%]

For comparison, the average movements in FDI for the 3 years to 2003

Outward FDI was $A 20,834 million

and the target countries by value were USA [55%], NZ [12%] and UK [9%]

This demonstrates that the outward flow of FDI is much less now than it was over a decade ago i.e

3.WHY OFF-SHORE INVESTMENT?

Why should we invest? There are a number of reasons which indicate that Australian companies should be investing in cross-border activities particularly in the emerging markets. Some of those reasons are explored.

- One is the current state of Australia’s globalisation. There are very few Australian companies which can be regarded as truly global, and by global, the company should be in at least 20 countries, and on at least 3 continents. It is difficult to identify 10 companies which fit into that category, however, compare this with a country like Sweden, half the size of Australia, not regarded as particularly innovative nor adventurous, but there are more than 10 [maybe 20] companies which would meet the criteria of being Swedish and global. The same could be said for the French, Italian, Swiss and many other smaller country companies which would fit the category of being global.

- It is easy to be blinded by very big resource companies like the BHP’s and the Rio’s and tend to overlook the fact that it is the operating companies which have to take a position in a foreign market and compete with both the domestic suppliers and other imports.

- However, within Australia, foreign companies have taken equity positions, and in almost every sector the significant companies are foreign-owned or foreign controlled. The central Europeans, Scandinavians along with the developed Asians of Korea and Japan have taken significant equity positions inside Australia. It is notable that over the last several years, various companies including the Canadians, South Africans and Spanish and more recently the Singaporeans and Chinese have been significant investors.

- That is not a very pretty picture. It paints Australia as a country which is seen as an investment target, with investors taking advantage of available resources and skills despite the relatively small market. Unfortunately, Australian companies are not reciprocating and are neither acquiring nor creating businesses in other markets.

- If this trend continues and we choose not to invest internationally, the end result is very clear. Australia earns little income from overseas investments or subsidiaries, but has to pay dividends, royalties and technical fees to foreign companies, which may or may not add to the tax collection pool.

- There is ample information which indicates that around 35% of the largest 2000 local and international companies are paying no tax at all in Australia [4]

- Common sense and logic says that the off-shore investment should be reasonably significant

This very much leads into the question of Why and also WHY NOT?

4. ADVANTAGES OF OFF-SHORE INVESTMENT

Why off-shore? The advantages of an off shore policy can be measured by a number of parameters, with the underlying assumption that the investment is undertaken with appropriate planning and execution

In addition to the significant benefits accruing to the home country, the benefits to the individual company which chooses to enter into another market and adopts a multi-domestic strategy are quite notable and can include;

- they are somewhat insulated from the cyclical nature of individual markets, as the cyclicality of various markets are not often synchronous

- it provides the perception to the market that it is a local company and is afforded the privileges of such

- being much closer to the market and customers ensures that the company has a good understanding of customer requirements and product suitability.

- Generally, it is an expansion to the home market

- it creates a stronger company which can more readily compete with global companies

The argument for an off-shore expansion or export activities is well covered in many articles, and the benefits if approached appropriately, are significant.

5. DOES EXPORTING CUT IT?

The response is a very qualified and hesitant yes. If the exports are supported by a physical presence in the target market so that a response to subtle market changes can be made, there is a knowledge and ability to respond to the customer, it is possible to protect the product IP, with or without legal protection, it is a physical presence in the market which offers protection. Anything less and there is the real risk of just developing the market for the international competitors.

There are many examples where a market is developed and is then hijacked by an international competitor. Similarly, we have seen too many instances where the product/service is “dumped” onto a market, without sufficient preparation, and expect it to take a place in that market. It may be acceptable for a while but it will surely be overtaken or overwhelmed.

6. WHY EMERGING MARKETS and WHY ASIA?

Asia is the fastest growing region in the world, and this is more than adequately demonstrated elsewhere, but factors such as large and growing populations, increasing disposable income, proximity to the home market, are some of the high points. What is not often understood is that the cultural climate may well be different and hence it may well be necessary to adapt your business to the local environment, as it is unlikely the local environment will adapt to you.

There are both positives and negatives associated with targeting emerging markets, but the positives can far outweigh the negatives. From a commercial perspective some of the positives include:

- Generally, they provide large and unfulfilled or only partially fulfilled markets with a population which is growing in both number and purchasing power, of course the downside is it may or may not have the expected nor developed distribution channels

- Generally, there is a wide acceptance of innovative and entrepreneurial actions, and the company and its services may receive a higher level of acceptance than might otherwise be expected.

- The growth in the overall economy will stimulate growth in your specific market to your advantage. This is a factor too often overlooked, as the growth in consumption generally gives the newcomer some time to adjust the strategy.

- The developing markets start from the current technology or state of development; they do not have to go through the full development cycle.

- To enter an expanding market often does not require shouldering somebody else aside, and in the early days it does not require special strategies, as long as the basics are in place.

The negatives usually, but not always, result from not undertaking or implementing the research appropriately, as this almost certainly results in a mismatch between the company and the market in which it is trying to establish

7. PERCEIVED IMPEDIMENTS

This is the crux of the off-shore development and in this section, the reasons which are often quoted as being impediments to an Asian investment are identified and explored. Those which seem to be regularly quoted are: –

[1] Australia does not have the funds to invest off-shore

[2] corruption is too daunting

[3] The Australian requirement to provide quarterly results

[4] Corporate taxation and lack of franking credits

[5] Regulations and red tape

[6] Too difficult

[7] A lack of a legal framework

The reasons postulated for the reluctance for off shore investment are evaluated in the following chapters

7.1 LIMITED FUNDS

The question of limited funds is explored in the following 2 sub-sections

7.1.1 MANAGED FUNDS

Australia is a wealthy country and has a particularly well-developed and active funds management industry. The Austrade publication “Australia’s Managed Funds, 2017 Update” [5] indicates that Australia has very significant funds, in excess of $A3 trillion and this is the 6th largest in the world and the certainly largest in the Asia-Pacific region.

The key drivers of the growth in the managed funds sector are the universal superannuation funds, and a well-developed insurance industry, and it is relevant to note that the compound annual growth of managed funds from 1991 to 2016 was 10.1%

There are several managed funds which target Asia, even so, the comment that Australia being a small country and not having the funds to invest does not stand up.

7.1.2 STOCK MARKETS

The stock markets in Asia are becoming particularly well established and attracting significant interest as well as providing capital for both corporate and national development.

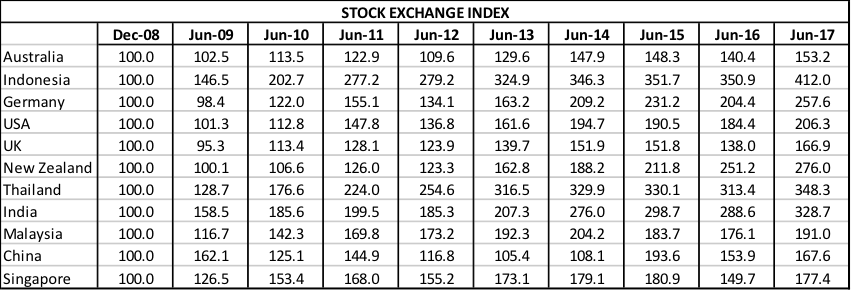

An analysis of the financial performance and outcomes of 6 Asian based stock markets and for comparison 5 western markets including Australia has been undertaken to evaluate the position [6]. The Asian and western markets selected for analysis were:

Indonesia JKSE Australia ASX200

Thailand SET Germany DAX

India BSE USA New York Composite NYA

Malaysia KLCI UK FTSE 100

China [Shanghai] 1. SS New Zealand NZX50

Singapore STI

In order to provide an analysis covering an extended period, the selected stock exchanges for the period from the end of the Global Financial Crisis taken as 1st January 2009 to the end of financial year June 2017 have been evaluated. For this Jan 1, 2009 is taken as 100, and the relative index for the individual exchanges at end of June for each of the subsequent years is shown in the following table.

The table shows annual change in the Index relative to the Jan 2009 Index.

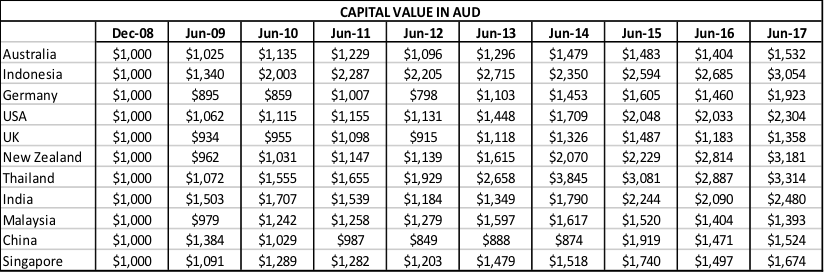

The changes in the currency valuations can significantly affect the capital returns when currency is moved across borders, and the effect of the currency changes is shown in the following table, which assumes that $A1000 capital is invested on Jan 1, 2009 and then shows the combined effect of stock market index changes as well as the changes in the relative value of the original $A1000 as at June each year is shown in the following table.

The value includes the stock market index and the value of the currency, but it does not include share splits, dividends, taxation and brokerage costs, although it may be argued that those other factors may have an effect on the share price and hence the index.

This demonstrates that on average the selected Asian markets had a higher capital growth than that of the Australian exchange, and the relative low performance of the Australian exchange is noted.

The reasons for the relative attractiveness of Asian stock markets are not explored here, but may include: –

- There are fewer investment alternatives to the stock markets in Asia

- It is less cumbersome to invest in the Asian stock market

- The companies are seen as well managed with significant benefits to the investor

There is insufficient information to be specific in relation to reasons for the relatively poor performance of the Australian stock market, however, the question about the managerial strategy and quality should be included in any evaluation of the reason for it.

With the funds available from the Managed Funds and the finance availability through the stock markets it is difficult to see that Australia’s reluctance to invest commercially is due to lack of funds.

7.2 CORRUPTION

The countries in the Asean region are approximately in the mid region of the Transparency International Corruption Index [7] although there are several which rate exceptionally well.

Corruption is often touted as an impediment to off shore investment and often rates highly on those scales which purport to identify impediments to off shore investment. The survey conducted by Austcham Asean earlier in 2018, showed that 47% of respondents indicated that corruption was a challenge to operating in Asean [8].

There is no question that corruption is a factor in the region, but is it a real impediment to commercial activities? Probably not. In Australia, a Royal Commission into the financial sector was conducted and the results have shocked many people as they were not aware of the extent of the corruption in the financial services sector. But business continues.

Over the last several years, I have undertaken several projects as follows:

- In Thailand, had the law changed at the request of an Australian corporate,

- In Indonesia, secured a major infrastructure project on behalf of an Australian corporate, and

- In Vietnam, secured a resource project from the government on behalf of an international company

And in each case, NO facilitation payments were made nor received, even though it might be expected by the reputation. Further during my 30 years in which many projects were undertaken in the region, NO facilitation payments were made in any form or in any circumstances.

There will be many reports of incidents in which corrupt practises occur but business continues despite this, and in most circumstances, business continues without being directly touched or disadvantaged by it. The Australian example demonstrates this, as does the fact that many companies are operating in the Asean region which is reported to be wildly corrupt, but they do so without being adversely affected.

7.3 REQUIREMENT TO PROVIDE QUARTERLY RESULTS

There is a requirement that publically listed companies provide updated financial results to the market on a 3 monthly basis. Some commentators see this as an impediment to participating in an off shore investment and unless it is expected to lead to a devaluation of the share price it is difficult to see that there is any impediment.

In any event, it is not taken as a legitimate impediment to off-shore investment in the context of this analysis

7.4 CORPORATE TAX & FRANKING CREDITS

The individual Corporate Tax structures and the lack of franking credits is occasionally proposed as an impediment to an off shore investment, and there may be legitimate reasons for such considerations. Australia, New Zealand, Chile, Canada, South Korea, UK, Germany and France have some form of imputation system. Most countries have a Double Tax Agreement [DTA] with their trading partners, all of which tend to reduce the tax liability by avoiding double taxation on dividends etc.

In another study it has been shown that there is NO tax liability for the 36% of the 2000 largest companies in Australia [4], and an investment in another tax jurisdiction may attract a liability, however, however, that hardly seems a reason not to invest.

Most of the developing countries in the region offer significant investment incentives, many of which include reasonably long tax holidays as part of the total package. The packages are country specific and are dependent on the product/service being offered, the location of the facility and there may be other factors. Never-the-less it can be a significant assistance in the investment decision and implementation.

7.5 DIFFICULTY AND RED TAPE

In almost every new investment, particularly a cross border one, the apparent red tape and difficulty which is presented may be seen as an impediment to business and it is often touted as such. Another study recently undertaken clearly shows that the major cost factor is what may be termed as Cost of Doing Business [CODB], all those regulatory impositions which add cost to any endeavour. [9]

The taxi service has been deemed the most likely business which can be legitimately used for cross border comparative purposes, for several reasons: –

- The service is basically common across the various countries

- The capital inputs are similar, i.e. a 5 seater motor vehicle, which are a common cost

- The major consumables, i.e. fuel, spares and replacement parts, should be a common cost.

- The taxi service generally is free standing business and is not part of an international ownership in which the operation and fare structure may be imposed from “head office”.

Any variations in those costs are almost certainly attributable to local requirements. The drivers labour cost can be identified and treated separately, and when the driver cost is taken away from the total fare income, the remainder has been termed CODB.

The average daily CODB for developed countries shown is approx. $A400 and for the developing countries it is $A100, which implies that the developed countries are at least 4 times the cost of the developing countries in relation to CODB. The cost of labour is a significant cost in the developed economies, but it is less than the CODB.

While the Taxi Analysis may be seen as “approximate” the differences are so significant that minor variations would not change the hypothesis; that the CODB in developing Asia is significantly less than doing business in a developed country. There are several interesting points of information

- The labour costs in Australia, and other developed countries while they may be significant, they are generally smaller than the CODB

- Presuming that the principles of this analysis can be translated to other operating or processing business, the CODB would probably be higher as there is usually real estate and buildings with the attendant costs to be considered, which is not a factor in the taxi business

- It is difficult to see that the CODB in Asia could be an impediment or a significant hindrance to an investment in the region.

The actual ratio of CODB to total cost is dependent on the industry, and it can be presumed that the labour intensive industries are going to have a lower CODB ratio than most other industries.

It is difficult to see that the “red tape” would be an impediment to an investment.

7.6 LEGAL FRAMEWORKS

Comments are often made that the Asian countries lacks a legal framework and that is a factor in the reluctance to invest. In fact, there are very few countries which lack a legal framework, but it may well be that the laws appear to be different, apparently stupid, irrelevant and may be ignored by others, but they are there, and as a foreign investor, must be adhered to. If the laws are inconvenient or impede the activities of the proposed investment, then it can be seen as an impediment to an investment and therefore the country should be avoided.

The resultant consideration is that in rare cases can the laws of an Asian country be seen as an impediment to the normal investment activities, however, if the situation does occur, then an investment should be avoided.

8. WHO DOES INVEST IN THE REGION

The global investment into the Asian region has been increasing rapidly both in revenue terms and the number of investments and investors, and this may be seen as an indicator of the relative ease of business formation, and the relative attractiveness of that economy for foreign investors. The source of FDI into the various countries, and the relative level for the year 2016 is: –

- Into Singapore; 52% by value are from USA, Japan, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Netherlands

- Into Malaysia 57% by value are from China, Switzerland, Singapore, Netherlands, Germany

- Into Indonesia 72% by value are from Singapore, Japan, China, Hong Kong, Netherlands

- Into Philippines 64% by value are from Netherlands, Australia, USA, Japan

- Into Thailand 69 % by value are from Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, Switzerland, USA

- Into China 81% by value are from Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, USA

These statistics indicate a reasonably wide spread of investors although the USA and Netherlands do appear to be significant investors in addition to Singapore and Japan

These statistics indicate that FDI or inward investment is a significant part of the economy of the ASEAN countries, so countries other than Australia apparently do not find it too dauntin9

9. LEADERS WITH ASIAN CAPABILITY

One of the perennial questions relates to the suitability of the business leaders for Asian operations and there are several in-depth analyses of the benefits of having Asia literate executives and advisors associated with the companies. A leadership which has a deep understanding of the specific Asian business culture, the good feel for the market requirements, and a long term view of business is necessary for success in the region. There are many examples of the results if any of those characteristics are missing.

The publication “Match Fit, Shaping Asia Capable Leaders” by PwC, Institute of Managers & Leaders, and Asialink Business [11] has quite a comprehensive and fact based research which supports the need for suitable experience. Other commentators are more forthright, Mike Smith former CEO of ANZ Bank has been reported in the AFR that the short term vision coupled with the compliance driven culture of corporate Australia has spawned accountants and lawyers rather than entrepreneurs onto the company boards [12]

This culture of “short-termism” encourages the board to be looking over the shoulder to the past rather than forward looking and may well be a factor in the reasons that Australian boards are not appealing to Asian entrepreneurs, as also a reason that corporate Australia is a reluctant international investor. Importantly, it may be a factor in the apparent poor relative performance of the corporates as indicated by share market index discussed in Section 7.1.1

It raises the question as to what can be done to overcome these apparent short-comings in Australia’s corporate psych

10. OBSERVATIONS

The author offers some observations about Australia’s commercial relationship with the region based on over 30 years working with companies which wish to establish or enhance their commercial presence in the region.

- The first observation is the number of significant public companies which have established an Asian presence and subsequently withdrawn from that particular market. The numbers are quite staggering, and some companies have failed attempts at multiple markets. Obviously it is not appropriate to mention names as the reason for the withdrawal is not known, but it is a significant number and it could be quite illuminating to understand at least some of the reasons.

- The second observation is the high number of smaller privately owned companies [SME’s] which are quietly working away in the regional markets. They may or may not have an equity connection back to an Australian company. In any event, the entrepreneur within these companies has seen the opportunities and taken the significant, and what could be seen as a very brave step, and established a commercial presence. They have braved the unknown, faced the “difficulties”, entered the market and ostensibly they are thriving.

- It is very difficult to quantify the number of these SME companies, but informed sources estimate that in Indonesia there are 600, and in Thailand there are 1250. This compares favourably with the number of Australian public companies in these 2 countries, less than 200 in each. Similarly, the large privately owned companies seem to be thriving and expanding in the region.

It would seem that Australian companies can be commercially successful in foreign markets as shown by the SME’s and to a lesser extent, the private companies

11. SUMMARY

The benefits of an off-shore expansion are quite extensive, however in the national interest the case for off-shore expansion and development of market expertise is compelling. Additionally, the benefits to the individual company can be quite extensive.

Despite this there is ample documentary evidence that corporate Australia avoids and is reluctant to enter into off-shore investments, particularly in Asia, despite the overwhelming calls to do so.

There are many issues which have been promoted as impediments, but none by themselves are sufficient reason NOT to invest. None of those “reasons” stand up to critical examination

Probably the most compelling reason is that other countries do not seem to have the same avoidance issues and are investing in the region, and when the FDI statistics for the developing countries are viewed there are some interesting investors. But of real interest is the fact that some of the countries which are avoided by Australian corporates are targeted by others.

In this paper, some of the purported reasons for the investment reluctance are explored and it is difficult to see them as real impediments, and hence, it is important to develop a programme to significantly increase the awareness, benefits and the appropriate actions to increase Australian corporate presence in the region. Australia has the ability to do this, but it will require government leadership and a sound policy together with a definite programme. The private sector will of necessity carry most of the burden, however, a programme of education and action needs to be developed and this will be the subject of a subsequent paper.

Glen Robinson B.Sc. [Tech] J.P.

26 July 2018

REFERENCES

[1] Passing Us By. PwC https://www.pwc.com.au/asia-practice/assets/passing-us-by.pdf

[2] www.oecd.org/investment/trade-investment-gvc.htm

[3] World Investment Report 2017 http://unctad/wir/2017

[4] https://afgventuregroup.com/dispatches/news/corporate-taxation-in-australia-for-the-year-2016/

[5] Australia’s Managed Funds 2017 Update https://www..austrade.gov.au/…/2017_Australias-Managed-Fund-Update.pdf.aspx]

[7] https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2017

[9] [https://afgventuregroup.com/dispatches/news/comparative-operating-costs-in-asia-2016/]

[10] https://en.portal.santandertrade.com/establish-overseas/XXXX/foreign-investment where XXX is the country under consideration]

[11] “MATCH FIT Shaping Asia Capable Leaders” by PwC, Institute of Managers & Leaders, Asialink Business https://asialink.unimelb.edu.au/stories/match-fit-shaping-asia-capable-leaders